Wow! So many lessons here. Let’s break it down.

Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error. Few people even want to admit their own mistakes, much less examine them to discover things about themselves and learn lessons from the experience. To learn from a mistake means I must accept the mistake as a mistake, as a failure of some kind. Then, I must avoid the trap of thinking of myself as a ‘failure’. I am not a failure, but what I did was a failure.

Philosophers throughout the ages have been saying the same thing, that we only learn from our failures, our mistakes. They also say that all of life is learning, and that when you stop learning, you begin dying. I think that is at least half true. You see, learning is one thing. Changing is another. Change is hard. It is even harder than admitting mistakes and learning from them. Learning and changing are two very different things, yet we have somehow arrived at a place where we think that learning inherently means changing for the better. Semantics at work. If we learn something but do not change our lives, did we really learn?

I learn things every day. But, do I embrace what I learn to the point that I let it change me, change my life?

The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice. He has supreme vanity. I readily admit I am not able to learn this lesson from Faulkner. First, what is a “good artist”? Am I a good artist? Frankly, I don’t consider myself an artist at all. I am not a wordsmith whose prose flows like poetry. I suppose I consider myself a storyteller rather than an artist.

Do I have supreme vanity, such that no one else is good enough to give me advice? Not hardly. In fact, this statement seems completely at odds with the idea that, as a good artist with supreme vanity, that I could even make mistakes. So, what would I have to learn? Dichotomy.

I prefer to believe here that Faulkner is trying to reference the great difficulty of having enough belief in myself that I am willing to place my written thoughts out there in public view for scrutiny and judgment by anyone. That, my friends, takes guts. It takes unassailable courage and the willingness to suffer. If you cannot suffer the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” then you do not wan to enter this particular race.

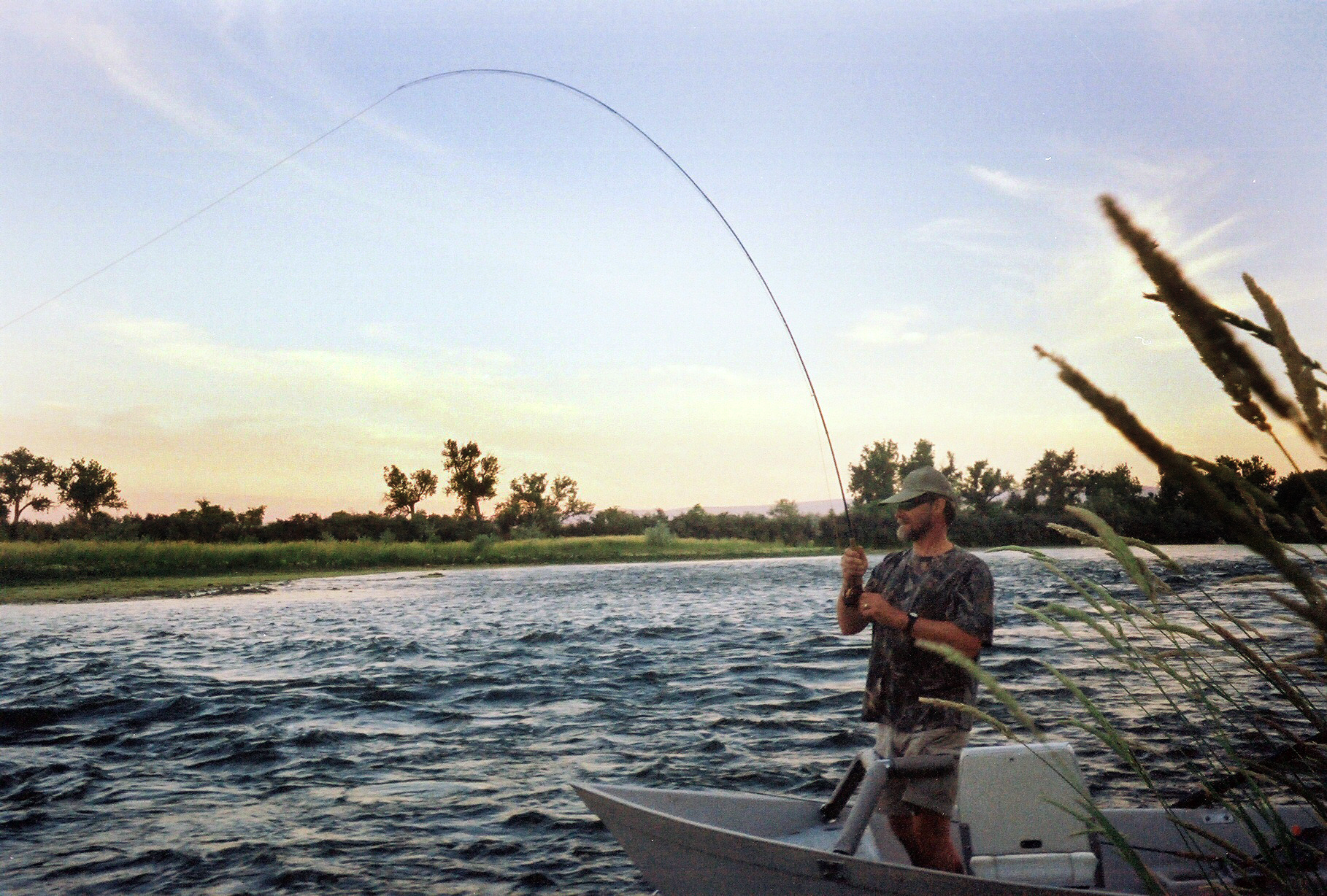

No matter how much he admires the old writer, he wants to beat him. That, right there, is why I started writing stories. Truth is, it is in my blood. My grandfather wrote stories from his life as a pioneer in the young Pacific Northwest. My father wrote stories, too. Some were true tales of their lives. Some were fiction made up based on incidents in their lives, or others pure fiction based on imagination. I didn’t know this until very late in life when both my grandfather and father had died and I inherited some of their things. No one else in my family wanted the old boxes filled with hand-written papers. When I opened them, I discovered a treasure trove of stories.

I always did love to read, though, and read prolifically from many genres. Some were good stories, well told. Some were good stories told poorly. Some were downright awful stories told terribly. One day, after finishing a poor story told poorly, I thought to myself, “Jeez Louise, I could tell a better story than that!”

My next thought was “Really? Did I really just think that?”

The truth is, it just pissed me off that some hack managed to get some dumbass agent to publish such a piece of excrement. I was angry about that, and it was my anger that motivated me to even consider the notion that I might write something myself.

Now, my grandfather, and my father, having no education beyond high school, both wrote exactly as they would speak the story. They just told the story, with no “pretty” words of description or deep-diving motivations. They wrote in oral tradition.

So, I dusted off one of my father’s stories, a western, and began to imagine how I could honor him by turning his story into a novel. Please understand, as an oral story, it was quite good. But as a written story, it was not so good. I sat in front of my computer and opened a word processing file and began. Several months later, I finished my first draft.

It was fun. It was terribly difficult. It was anguishing and exulting at the same time. No one had ever told me it would also be addictive. I cannot stop.

I once told the story of how I began writing to some fellow novice writers in an online group, of how anger was my beginning motivation. Hoo-wee! You would have thought I threatened to bomb somebody! They were outraged that I would even admit that “anger”, that horrible and negative reactive emotion, could possibly be motivation for something as pure and enlightened as “writing”. How ignoble of me. Yes, one of them literally used that phrase.

I ignored them and kept writing. You see, it doesn’t matter where we get the original motivation to begin. What matters is that we begin. And we keep with it. For me, it was like Faulkner’s phrase in that I thought I could do it better than “the other writer”.

Well, I guess that is enough risky thought-writing for one day. Party on, dudes!